For too many, loneliness is a fact of life and the project From Isolation to Inclusion is designed to change that. Now, the partners are finding that the new constraints of 2020 can be thought of as creative challenges in combatting social isolation.

At its outset, work in the project From Isolation to Inclusion (I2I) was supposed to be challenging but relatively straightforward. After all, the problem we were facing was a growing one already before Covid-19:

More than 75 million Europeans only see their family once a month or less. Social isolation affects our physical and mental health.

Like smoking or physical inactivity, it can even increase our risk of early death.

We set out to counteract loneliness in communities and neighbourhoods across the North Sea Region, and help the public sector find new innovative ways of social inclusion.

Meeting the covid constraints

We were going to go about this using co-creation methods. This involves a joint effort of citizens, the public sector and voluntary sector professionals in all the steps of creating a new public service: From initiation through planning, design and finally, implementation.

As the North Sea Region started locking down in March, it became apparent that even a simple thing like going out to meet people and talk to them was suddenly difficult.

Together, we tried to reframe the problems we were facing and see them as opportunities. The partners were already seeing changes in their organisations, which were adapting to work in new ways.

Värmland visualised

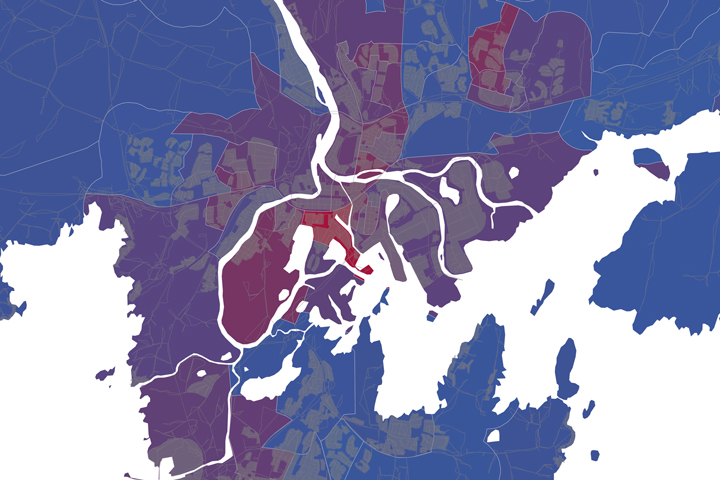

In Sweden, Region Värmland is now able to visualise population demographics on a much more local level than before, with a new digital tool developed as part of the I2I project. This will help the region take a more place-based approach than before. Why, for example, can we see higher concentrations of people living alone without children in some places compared to others? Where can we see small local areas with increased risks of social isolation and loneliness?

During the pandemic, Region Värmland has developed new, digital tools for identifying target groups on a hyperlocal level. This map shows the concentration of people living alone without children in Karlstad, Sweden.

Project leader for Region Värmland Fergus Bisset says, “this new digital tool has helped us see the problem differently and will allow us to reach out to these local communities much more closely, especially now during the pandemic. We can develop deeper partnerships with the community organisations already working in these places to tackle this problem together in the next stages of the project.”

Also, loneliness is part of the public conversation in a way that nobody had anticipated only twelve months ago.

And so, with the challenges created by Covid-19, we have had to ask ourselves:

- How might we work more outside?

- How might we work with members of the community to make more contributions before or after meeting with us?

- How might we do more stuff using physical materials, rather than just meeting and talking?

- How might we do more stuff using virtual tools?

- How might we gather more personal and reflective insights, instead of group-based co-creation?

Danish DIY

Aarhus municipality, the Danish partner in I2I, decided on starting a DIY community for young people. Social gatherings in Denmark outside private homes are limited to ten people.

This limit is especially hard on young people, researchers have found. After all, social relations among young people are continually changing.

To facilitate a community for younger people, an initiative called Genlyd started a DIY club, something that was already trending among younger people on social media. After a four-day campaign, the first three workshops were fully booked.

At a DIY session in Denmark, young people are encouraged to create their own network of likeminded creators.

There was always the risk that the participants had fun but went back to their lonely lives after the workshops were over. Therefore, Genlyd created a DIY community where young people can reach out to others and start creative communities of their own.

A neighbourly visit

To learn what people need, you have to talk to them. Therefore, the Belgian city of Aalst has been going door to door to conduct interviews on social inclusion this fall.

Workers going door to door in the City of Aalst in Belgium. The new situation turned out to be perfect for discussing social relationships and mental health.

These short conversations with residents on their doorsteps turned out to be very useful. Among other things, the interviewers wanted to know about the residents’ social relations, and if they felt at home in the neighbourhood.

In one case, this even led to a connection between two of the neighbours:

“They both told us that they wanted to get to know each other but had not taken the step yet. I informed one of them that her neighbour was thinking the same, and she promised me to ring her doorbell,” says Gwen Vanderstraeten, the project leader in the City of Aalst.

It turned out that the coronavirus situation brought a unique opportunity to discuss social relationships and mental health openly – literally at residents’ doorsteps.

We need both buses and social groups

The partners are also using this time to learn from each other. Not least from the British partner Campaign to End Loneliness, which just launched their new report “Promising approaches revisited: Effective action on loneliness in later life”.

As Robin Hewings writes, the key is that to tackle loneliness, different types of support need to be in place:

“We need to find people and listen to their needs. They need to have the infrastructure to engage in social life, whether that’s about digital, transport or a built environment that supports social life. Finally, there are direct ways of reducing loneliness whether that is one-to-one or in groups, or psychological support.

“The framework avoids comparing apples with oranges. Befriending and social prescribing cannot be directly compared – but do go together. Similarly, buses are not better or worse than social groups – we need both.”

ABOUT I2I

From Isolation to Inclusion (I2I) seeks to counteract loneliness in communities and neighbourhoods in the North Sea Region. Together we are working to help the public sector innovate in the area of social inclusion. We do this by working with academia, municipalities, businesses, and the people afflicted by social isolation.

About the author

Walter Wehus is a communication advisor at the University of Agder and works with communication in the I2I project. The object looming behind him is a coronavirus Christmas decoration by Kristiansand artist Erik Pirolt.