The North Sea Region Programme supports innovation that reduces the heavy CO2 footprint of sea carriers. An example is the SAIL project (2012-2015) that helped kick-start wind-assisted shipping propulsion (WASP), a low-carbon freight solution which is now in growing demand. This project also played a core role in the early formation of the International Windship Association.

If the term ‘sailing ship’ brings 18th century ships and pirates to mind, think again: The Age of Sail has returned in an entirely new shape. Advanced sailing vessels are emerging on the market that rather look like something from a science fiction movie, with cylindrical rotor sails in futuristic shapes replacing the traditional sailcloth. The driving force behind this development is the need to reduce the significant CO2 footprint of maritime shipping.

Cargo ships are causing 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions and this is projected to grow.

SAIL: providing evidence

Wind-assisted shippping propulsion (WASP) was just taking off when SAIL (2012-2015) set out to explore the concept. The project developed novel WASP designs and demonstrated their feasibility by testing their technical features and exploring business cases. The project provided some of the earliest proofs of concept contributing to the evolution of WASP.

The SAIL team prepares for a wind tunnel test.

Beyond this trailblazing work, the project was successful in raising awareness amongst sea ports, e.g. the Rotterdam Sea Port promised to lower its fees for the Ecoliner model featured in this video:

Trials and tribulations

However, the project faced some challenges in bringing the windship models onto the market. ‘We found the best performing model for long-distance ocean travels was the Dyna Rigg with a capacity of up to 8,000 tonnes of cargo. However, building it would cost 23 million euros compared to only 14 million for a traditional ship. With such a huge difference in construction cost, the Dyna Rigg is a difficult sell ,’ explains Robbert van Hasselt who led the SAIL project on behalf of the Dutch Province of Fryslân.

He also points towards the oil prices that have plummeted in recent years. ‘This favours old-style ships running on oil and puts a brake on the market for new models with no or little use of fossil fuels’.

WASP model makes it to the market

Fortunately, these setbacks did not stop the ball from rolling. As part of the project, the SAIL partner C-Job Naval Architects developed the first designs of the nimble Flettner model. The project tested its performance and found this model to be the most profitable option for short-distance travels in the North Sea Region.

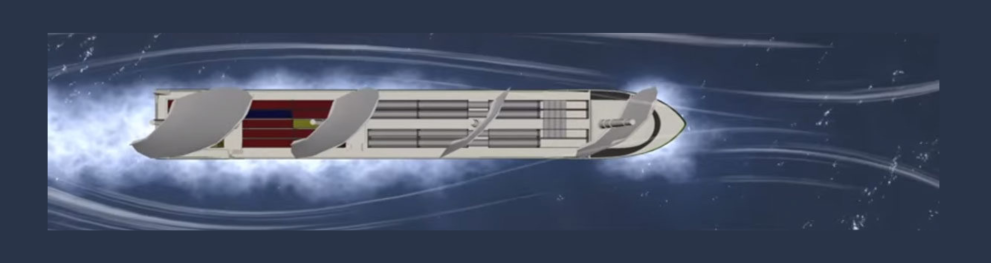

Another project partner, the Dutch company Switijnk Shipping (formerly Ameland) subsequently commissioned C-Job to deliver a Flettner design tailored to their requirements which optimises the benefit of the rotors. The design – a new and larger model based on the original Flettner model – was delivered in February 2018, three years after the closure of the SAIL project.

We see a growing interest for this type of solution from several industries and vessel sizes, including tankers and ferries. And we are able to develop designs and solutions tailored to specific ship owner needs. The SAIL project prompted us to set up our own research & development department and build our capacity to innovate.

The lightweight Flettner vessel designed by C-JOB for Switijnk Shipping. It is based on the model developed for the SAIL project. Photo: C-JOB Naval Architects.

Industry initiatives are important

According to Robbert van Hasselt, an international carbon tax would make the wind-assisted ships competitive. "Ships that don’t emit any CO2 or nitrogen oxides are not rewarded within the current framework. The carbon credit system is national and not designed for freight carriers that move across borders. Green maritime transport options need to be better incentivised."

Despite its clear role in climate change, commercial sea transport is excluded from the Paris climate agreement. So how can WASP be fast-tracked?

Robbert van Hasselt emphasises the role of business: "Freight owners and retailers can influence the market by adopting sustainability policies including climate-friendly transport. They are the customers of the shipping industry, so their demands are a strong driver." An example of this is the chocolate brand Tony’s Chocolonely. This company works to decarbonise its cargo transport, aiming for a carbon-neutral ‘bean to bar’ supply chain.

Fostering community and business interest

SAIL also made its entrance at the United Nation’s International Maritime Organization (IMO) and was strongly engaged in the newly established International Windship Association (IWSA).

Secretary of IWSA Gavin Allwright says: "The SAIL project created a lot of interest among advocates of low emissions shipping and brought together a diverse group of stakeholders that would not usually have worked together. The publicly accessible reports and work done on the technical, routing, and economic side certainly impacted both the industry and the many wind propulsion projects that were outside of the project, showing a clear and well-calculated model of how WASP could operate in the existing shipping paradigm and the types of vessels and operations that would be required to make both a profitable and resilient business model for these types of ship."

Most importantly, SAIL generated interest amongst businesses. For example, some of the most important sea shipping safety certifying organisations – GL, IRENA, and Lloyds – were prompted to conduct feasibility studies on their own initiative.

The Ecoliner was one of the designs that SAIL developed and tested for its feasibility. Design by DYKSTRA Architects.

Allwright adds: "The outcomes of SAIL contributed greatly to the development of a WASP community. While the early origins of IWSA came from work that the initial founders were undertaking, a sizeable number of the early members of IWSA and the community spirit came from the SAIL project activities. These intangible outputs and network of the SAIL project were an integral part of the early formation of IWSA and many members and advisors of SAIL have continued to engage with IWSA activities."

A recent EU-commissioned report envisages up to 10,000 wind propulsion installations at bulkers and tankers by 2030. Allwright: ‘‘EU funding is important in the further promotion of WASP. IWSA is developing regional hubs for taking WASP development forward and these will likely be fundable through Interreg. The development of the sector is at a critical stage where we are moving strongly towards sea trials, demonstrator vessel development and creating market-ready technologies. EU support is vital if we are to reach the type of development that the report outlines."

The North Sea Region Programme continues its support to low-carbon freight shipping in the North Sea. The DUAL Ports project includes the SAIL cargo pilot that seeks to develop sailing hubs at small North Sea ports, providing small businesses with a sustainable cargo shipping solution, and to design a wind-propelled boat for small business trade in the North Sea. Also, Robbert van Hasselt now leads the #IWTS 2.0 project that promotes the use of inland waterways for transporting goods and exploring sustainable concepts for small barges.